Immutability is powerful, but it’s a rather blunt tool, and not suited to every single onchain application. Production software has bugs, parameters need adjustments, and protocols evolve. When a critical vulnerability appears or a market setting must change immediately, immutability can force painful migrations, complex state transfers, and prolonged downtime. For many teams, the better tradeoff is controlled upgradeability, which allows for the preservation of onchain state and address continuity while swapping the logic that runs against that state.

Upgradeable Smart Contracts: Proxies, Patterns, Pitfalls and CI/CD Safeguards

Immutability is powerful, but it’s a rather blunt tool, and not suited to every single onchain application. Production software has bugs, parameters need adjustments, and protocols evolve. When a critical vulnerability appears or a market setting must change immediately, immutability can force painful migrations, complex state transfers, and prolonged downtime. For many teams, the better tradeoff is controlled upgradeability, which allows for the preservation of onchain state and address continuity while swapping the logic that runs against that state.

Upgradeable smart contracts

In this post, we’ll explore how upgradeable smart contracts and proxy patterns work under the hood, the security pitfalls and threat model to be aware of, and best practices to follow when utilizing upgradeable smart contracts. We’ll dive into the main proxy patterns, discuss storage layout and governance considerations, outline a step-by-step upgrade process, and answer some frequently asked questions.

By the end of this article, you’ll understand how to harness upgradeable contracts without compromising on security and how Octane can help enforce these best practices automatically.

How proxy patterns work

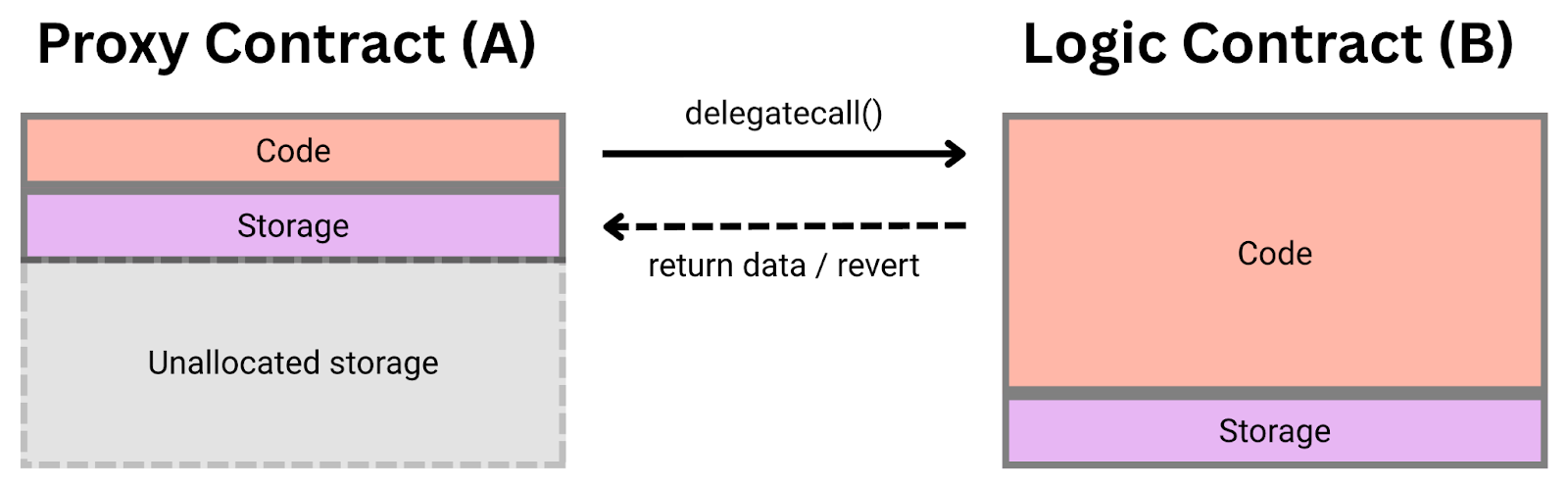

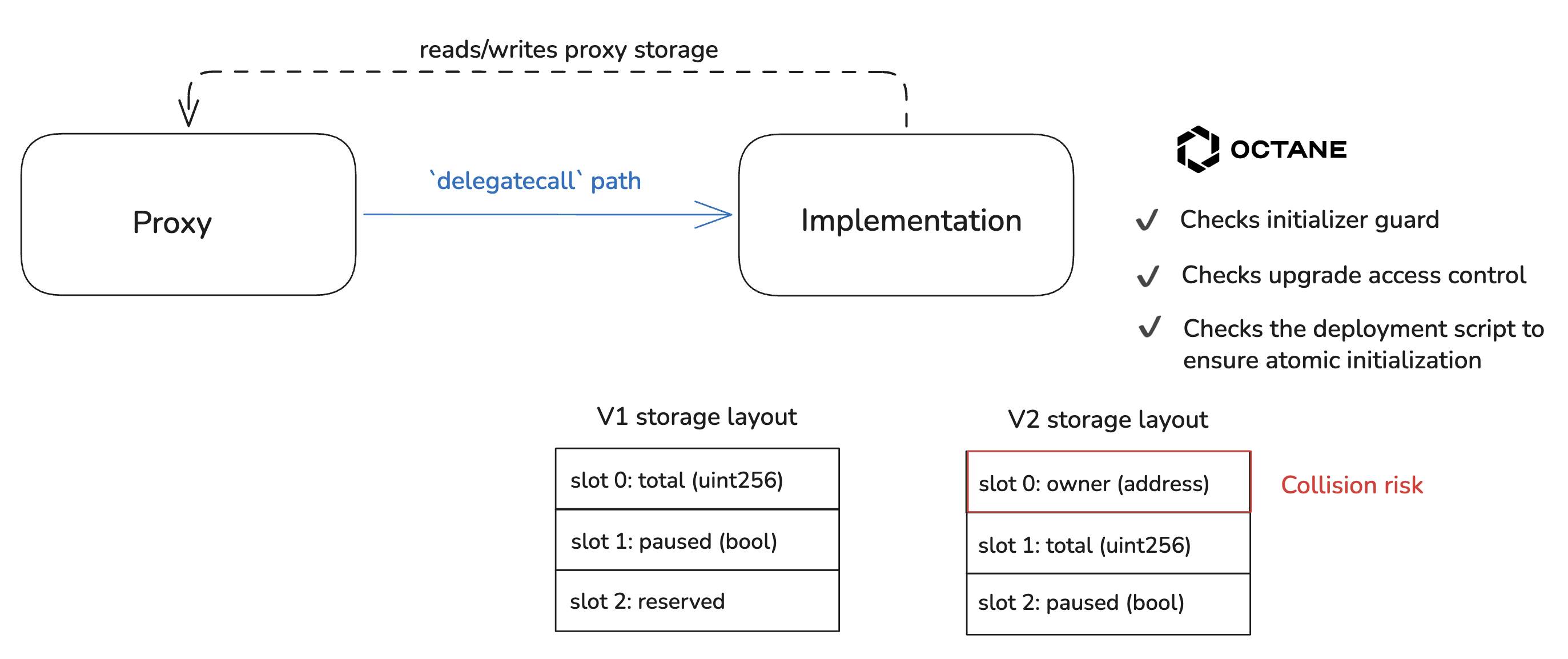

An upgradeable setup splits a contract into two pieces: a proxy and an implementation. The proxy holds state and assets (storage, balances, ETH); the implementation (logic contract) holds the code. When a user calls the proxy, its fallback delegates the call via (you guessed it) delegatecall to the implementation, preserving msg.sender and msg.value and executing in the proxy’s storage context. In effect, the proxy is a thin shell; all state writes land in the proxy, while the implementation remains stateless. Upgrading means updating the proxy’s implementation pointer (often with upgradeTo/upgradeToAndCall).

Crucially, because the implementation’s constructor never runs when called via a proxy, upgradeable contracts use initializer functions instead. The community standard EIP-1967 reserves specific storage slots in the proxy for the implementation address and admin address, to avoid storage collisions with application state.

Tip: Use an initialize() function (with an initializer modifier) for setup, and have the logic contract’s constructor call _disableInitializers() to lock it down. This prevents anyone from directly initializing the logic contract and tampering with your upgrades.

In practice, teams typically choose one of three proxy patterns:

- Transparent proxy: The upgrade functions (e.g. to change the implementation) live in the proxy contract, often mediated by a separate

ProxyAdmincontract. This is a simple operational model: calls from the admin are recognized and handled by the proxy (rather than forwarded), while regular user calls are always delegated to the implementation. The separation between admin and user call paths avoids certain conflicts. - UUPS (EIP-1822) proxy: The upgrade logic lives in the implementation contract itself – usually functions like u

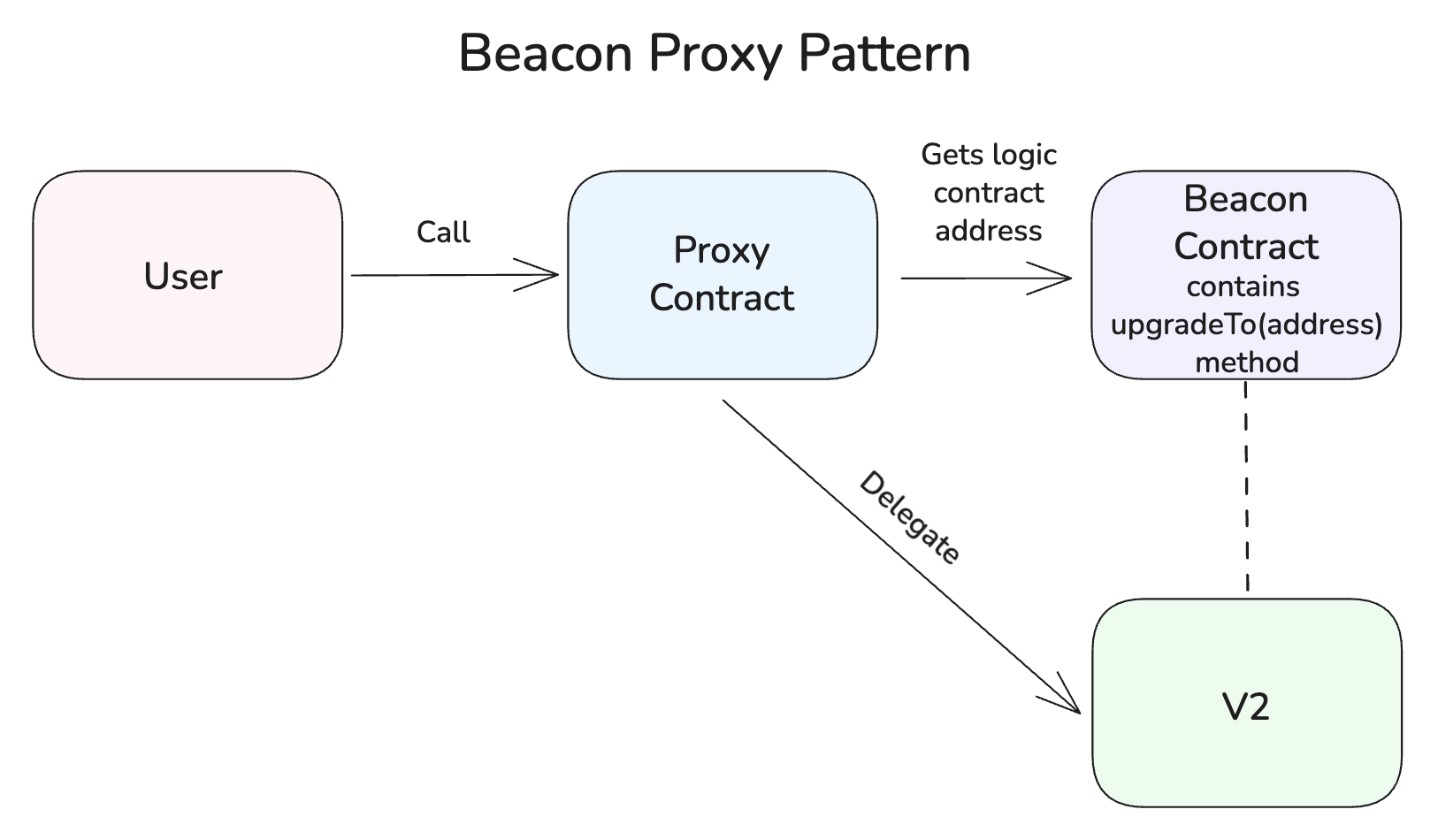

pgradeTo(address newImpl)plus an access control mechanism (_authorizeUpgrade) and a proxiable UUID for safety. This yields a slightly leaner proxy (no admin logic in the proxy) and allows the implementation to potentially lock or disable further upgrades. However, because the implementation governs its own upgrades, you must implement proper access control (e.g. restrictupgradeToto only be callable via a proxy, using anonlyProxymodifier) to prevent someone calling the implementation directly and bricking the upgrade path. - Beacon proxy: This pattern introduces a third component, a Beacon contract, which holds the address of the current implementation. Many proxy instances can point to the same Beacon. Upgrading the Beacon then updates the implementation for all its proxy dependents in one transaction. This trades granular control for scale – it’s efficient when you have numerous identical contract instances that should all upgrade together, but it also means a bad Beacon upgrade can break every proxy at once (a shared failure domain). Each

BeaconProxystill needs to be initialized individually, since upgrading the Beacon doesn’t re-run any initializers on existing proxies. (Typical tooling like OpenZeppelin Upgrades plugin for Hardhat or Foundry supports all these patterns, and also performs compile-time or deploy-time checks for storage layout compatibility and initializer usage.)

Threat model for upgradeable systems

There are critical security risks to manage in any upgradeable contract system. Key threats include:

- Admin key risk. If a single externally-owned account (EOA) can upgrade the contract, that key is effectively holding a “hot wallet” that can change contract logic at will. A compromise of the admin key could be catastrophic. Use a multi-signature wallet for the admin, and enforce a timelock on upgrades to mitigate this risk.

- Uninitialized implementation or proxy. If the proxy or the logic contract isn’t properly initialized and locked, an attacker could call the initializer and take ownership. This is exactly what happened in the Parity multi-sig wallet incident in 2017. An attacker noticed the library contract was uninitialized, initialized it to become the owner, and then invoked a

selfdestruct, permanently freezing ~$150 million in Ether. Always initialize your proxy (or implementation, in UUPS) as part of deployment, and call_disableInitializers()on the logic contract. - Storage layout collisions. If you change the order or type of state variables between upgrades (or introduce new stateful base contracts) you will shift storage slots and likely corrupt the contract’s state. The rule is append-only for storage: do not reorder existing variables, only add new ones to the end, and maintain a reserved

__gaparray if using OpenZeppelin’s pattern to fill unused slots.

- Initializer bugs. Initializers are easy to get wrong. Common failures: (1) not initializing all parent contracts in a multiple-inheritance graph, (2) allowing the same initializer to run twice, (3) introducing reentrancy or unsafe external calls during init. Use OpenZeppelin’s

initializerand versionedreinitializer(n)modifiers to guarantee one-time execution per version, and call every required parent initializer exactly once (e.g.,__Ownable_init(),__UUPSUpgradeable_init()). Keep init logic internal, preferonlyInitializinghelpers, set critical state before any external interaction, and in the implementation’s constructor call_disableInitializers()to lock the logic contract. - Function selector clashes & metamorphic behavior. The proxy and implementation share the same function namespace. A poorly designed implementation could inadvertently have a function that shares a selector with one in the proxy’s interface (like

upgradeTo), causing conflicts. Also, an implementation might usedelegatecallto arbitrary addresses or even self-destruct – which can be abused to metamorphose contract behavior. Avoid defining functions in the implementation that collide with proxy/admin function selectors. - Beacon shared risk. If you use a Beacon proxy setup, remember that one bad Beacon upgrade will impact every proxy that depends on it. The Beacon’s admin controls are effectively root-level privileges across the system, so treat the Beacon admin with the highest security (multi-sig + timelock, just like a core contract).

In summary, your continuous integration (CI) pipeline or review process must block upgrades or deployments that violate these rules – e.g. a weak admin key setup, missing initializer protections, detected storage layout incompatibilities, or unsafe opcodes in the diff.

Pattern deep dives

Let’s examine each proxy pattern in a bit more detail, including how they work, how they can fail, and what to check in CI:

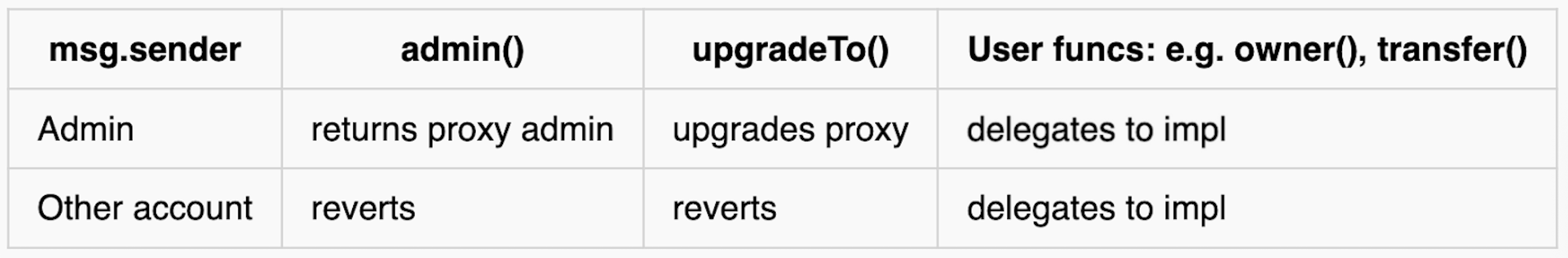

Transparent Proxy

- Mechanics. The proxy contract owns the

upgradeTo(and related) function. Only an admin (often via aProxyAdmincontract) can call upgrade functions; regular users never interact withupgradeTodirectly. The proxy’s logic is: if the caller is the admin, handle the call in the proxy (for upgrades or admin changes); otherwise, delegate everything to the implementation. This ensures admin and user call paths are separated cleanly. - Failure modes. An admin might accidentally interact with the contract in the wrong way – e.g. calling a function meant for users but from the admin address, which in a Transparent proxy pattern will not be delegated (because admin calls are intercepted by the proxy). Also, forgetting to initialize the separate

ProxyAdmincontract is a common oversight. Another pitfall is leaving constructors in the logic contract; they won’t execute via proxy and can indicate mistaken assumptions. - CI checks. Ensure the proxy’s admin and user call paths are properly separated in tests (the admin should never accidentally trigger user-delegated logic). Verify that no public or external function in the implementation can be used to upgrade the contract (i.e. no

upgradeToin the implementation for Transparent proxies). Deploy scripts or CI should enforce atomic initialization – e.g. usingProxyAdmin.deployProxyorupgradeAndCallto initialize the proxy in the same transaction as creation, so it’s never uninitialized.

UUPS (EIP-1822)

- Mechanics. In UUPS, the implementation contract itself implements the

upgradeTofunction (and usually an eventupgradeTo(address)and a proxiable UUID getter). The proxy is very minimal – it basically just delegates calls. The implementation’supgradeTotypically usesonlyProxy(a modifier that allows it to be called only via adelegatecall, i.e. only when invoked through a proxy) and an_authorizeUpgradefunction (usually to restrict access to an owner or admin) to control upgrades. - Failure modes. The most common UUPS mistake isn’t a direct call to

upgradeToon the implementation (withonlyProxyit should revert, and without it the call merely mutates the implementation’s own ERC-1967 slot while leaving the proxy unchanged) but an upgrade routed through the proxy without strict guards. IfonlyProxy/_authorizeUpgradearen’t enforced and the candidate isn’t validated viaproxiableUUID(), an attacker or misconfig can swap in an arbitrary or non-UUPS target and brick the system. A second failure mode is mismatched inheritance: shipping a version that drops or renames the UUPS hooks (upgradeTo,_authorizeUpgrade,proxiableUUID()) lets you upgrade to that version but not beyond it, meaning the proxy’sdelegatecallwon’t find the hooks next time, and the path dies there. Finally, keep implementations initialized and locked: initialize logic contracts and call_disableInitializers()in their constructors, and perform proxy initialization atomically (e.g.,upgradeToAndCall/deployProxy). Leaving an implementation uninitialized has caused real-world takeovers and freezes (cf. the Parity library incidents). - CI checks. Assert that every UUPS implementation includes the

onlyProxy(or equivalent) in itsupgradeTo/upgradeToAndCall, and that_authorizeUpgradeproperly restricts access (e.g. to the contract owner or a designated upgrader role). Verify that theproxiableUUIDremains consistent across versions – changing it would make the proxy refuse to upgrade (as a safety measure defined in EIP-1822). Essentially, keep all the UUPS upgrade hooks in place and identical in each new implementation. Your CI can diff the new code to ensure that the UUPS-specific functions (upgradeTo,proxiableUUID, etc.) haven’t been altered or removed.

Beacon

- Mechanics. A Beacon is a single contract that stores the address of the current implementation for a given module. Many proxies (often called BeaconProxies) can all point to this Beacon contract. When a BeaconProxy receives a call, it asks the Beacon for the implementation address, then delegates the call to that implementation. Upgrading means the Beacon’s owner calls the Beacon’s own

upgradeTofunction, which changes the stored implementation address – instantly routing all the BeaconProxies to the new logic. - Trade-offs. The Beacon pattern centralizes upgrade administration: one upgrade transaction to the Beacon can update N proxies at once (convenient for say 100 clones of the same contract). However, this also means one mistake can affect N instances. It’s great for operational efficiency and consistency across many instances, but you must treat the Beacon with the same security as you would if all those contracts were a single contract – because in effect, they are tied together.

- CI checklist: When using Beacons, enforce all the usual access controls on the Beacon itself (the Beacon should typically be owned by a multi-sig or governed by a DAO with a timelock). In addition, test upgrade rollbacks and emergency recovery: if an upgrade via the Beacon fails or is malicious, do you have a way to quickly point it to a safe implementation? Perform role-based access tests to ensure only authorized personnel can call the Beacon’s upgrade function. And just as with other patterns, ensure that no direct

upgradeTofunction is accessible on the BeaconProxies (they should only upgrade via the Beacon). Because of the shared risk, some teams even implement a “pause all” switch or emergency stop in the proxies that can be triggered if a bad Beacon upgrade is detected, buying time to fix it.

Storage layout safety

When evolving an upgradeable contract, maintaining storage layout compatibility is paramount. Here are some guidelines to avoid state corruption on upgrade:

- Keep storage append-only. Never remove or reorder existing state variables. If you must deprecate a variable, you can stop using it, but do not physically remove it from the contract’s code – that slot must remain occupied to preserve the layout. Avoid adding new stateful base contracts (parent classes that introduce their own storage) because that can insert variables before your existing ones. A common technique is to include a fixed-size

__gaparray (e.g.uint256[50] private __gap;) in your contracts, which you can gradually fill with new variables in future upgrades if needed – this reserves storage slots to accommodate growth. - Automate a storage layout diff on every code change. As part of CI, run a tool to compare the storage structure of the new implementation against the last deployed version. OpenZeppelin’s plugins and Foundry’s built-in tools can do this. If any incompatible change is detected (type change, order change, etc.), that should be treated as a deployment-blocking issue. Additionally, always dry-run your upgrade on a testnet or fork with a copy of real data to ensure that the new implementation doesn’t break the state.

- Monitor gas usage of critical functions pre- vs post-upgrade. Sometimes a seemingly innocuous change can dramatically increase gas cost due to changed storage patterns or added logic. By measuring the gas usage of important functions before and after, you might catch issues (for example, an added loop that makes a function dangerously expensive). A significant gas delta could hint at a storage issue or an unintentionally expensive code path introduced in the upgrade.

Governance and operations

Deciding how upgrades are administered is as important as the code itself:

- Admin controls. Use a multisig or decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) as the upgrade admin, never a single EOA. Introduce a timelock delay for any upgrade actions – this gives users or auditors time to react if a malicious or accidental bad upgrade is proposed. Also, if the contract was initially deployed by a single key (as is common), transfer the ownership/upgrade role to the multisig or DAO as soon as possible after deployment, so the deployer key is not lingering with powers.

- Rollout discipline. Treat upgrades with the same caution as deploying a brand new contract. Consider staged upgrades: for instance, upgrade a single “canary” instance or a subset of your contracts first, verify everything works in production, and then roll out to all instances. If possible, design your system with a pause or emergency stop that an admin can trigger if something goes wrong, and even a rollback plan (keep the previous implementation address handy and compatible) to revert to a known good state if an issue is discovered.

- Post-upgrade verification. After an upgrade transaction executes, subscribe to events like

Upgraded(address newImplementation),AdminChanged, and (for Beacon)BeaconUpgraded. These events should be emitted by OpenZeppelin’s proxy contracts or similar standards. Your monitoring should alert the team whenever an upgrade happens on mainnet – especially if it was not expected – and you should immediately verify that the new implementation’s code matches what was intended (e.g., compare the deployed code hash to your audited code). Also double-check that the proxy’s state (such as the admin address) did not unexpectedly change.

CI/CD hardening for upgrades

Given the risks, your CI/CD pipeline should actively enforce upgrade safety. Some recommended checks and automations:

- Pull request gates. Every PR proposing a contract change should run a storage layout compatibility check. If the layout doesn’t match the previous version (except for allowed additions at the end), the PR should fail or at least flag for intense review. Also enforce that any new initializer is properly protected (using

initializermodifiers), and that noselfdestructor low-leveldelegatecallsneaked into the code. Essentially, CI should be your first line of defense against coding patterns that could break an upgrade. - Example failures to test for. Simulate scenarios like: an initializer that was left

public(which would allow anyone to initialize the logic contract); an implementation where_disableInitializers()was not called in the constructor (meaning an attacker could potentially initialize it later); or a storage type change (e.g. changing auint256touint8) which will corrupt data. These are not theoretical – such mistakes have occurred in real projects. Make sure your test suite or static analysis catches them. - Autofix path. Some upgrade issues can even be auto-corrected by tooling. For example, if your new implementation is missing the

onlyProxymodifier on a UUPSupgradeTofunction, a smart tool can insert a default one. If you forgot to reserve storage with a__gapin a base/upgradeable contract, a tool could suggest adding it to reserve storage. Octane’s platform goes further – it can detect a missing parent initializer call or an unsafe storage change and directly propose a patch (diff) to fix it. Embracing such automated fixes in your CI can make the upgrade process much safer and faster.

When not to use upgradeability

Despite all the benefits of upgradeable contracts, there are cases where you should not make a contract upgradeable:

- Ossified cores and finality. If a contract is truly core to your system’s value (for example, a token contract with a fixed supply and behavior, or the core logic of an AMM with established math), users derive confidence from its immutability. Once it’s battle-tested, you might deliberately choose to ossify it – that is, make it impossible to upgrade further. For anything that requires strong social consensus to change, prefer an immutable contract and, if needed, deploy a new contract for major changes (with a migration path) rather than an upgradable one.

- Alternative patterns. Sometimes you need flexibility but want to avoid the complexity of proxies. Possible alternatives include module/plugin systems, the Diamond proxy pattern (EIP-2535) which uses multiple facets to compose a contract, or simply using on-chain configuration to tweak behavior (as opposed to upgradable code). Each alternative comes with its own risks: e.g., Diamonds allow many facets but require careful management of multiple modules and a more complex storage scheme; configuration-driven systems avoid code change but might be limited in what they can do. These approaches can introduce even larger upgrade surfaces or more complicated audits. Use them only when proxies don’t fit the need, and be prepared for even more scrutiny on their security.

In short, if the logic truly never needs to change or the cost of an exploit outweighs the benefit of quick updates, it’s better to deploy immutable contracts. Upgradeability is a tool; use it when it makes sense, and avoid it when it doesn’t.

Implementation checklist

To wrap up, here’s a high-level checklist for deploying and managing an upgradeable smart contract system:

- Pre-deploy: Decide on your upgrade pattern (Transparent, UUPS, Beacon). Write initializer functions for your contracts instead of constructors. Add a

__gapin each storage-heavy contract for future-proofing. Plan the admin key handoff (who will own the proxy initially and who it will be transferred to).

- Deploy: Deploy the implementation contract(s) first. Then deploy the proxy pointing to the implementation (if using Transparent, via a ProxyAdmin; if using UUPS, consider OpenZeppelin's

deployProxywhich handles the flow). Call the initializer function to set up state atomically with proxy deployment (most upgrade plugins have an option to callinitializeduring deployment). Finally, transfer the proxy’s admin role to the intended multisig/DAO (the deployer should renounce ownership if they were temporary).

- Operate: Monitor for any

Upgradedevents or admin changes on your contracts (set up alerts). Keep an eye on public channels for vulnerability disclosures that might affect your contracts, since you have the ability to upgrade if needed. Ensure your upgrade keys (multisig) are safe and that signers know their role.

- Pre-upgrade (for each upgrade): Before pushing a new implementation, run a storage layout diff between the current and new versions. Run your full test suite with the upgrade applied (many frameworks allow you to simulate upgrading a proxy to the new logic on a fork or in tests). If possible, deploy the new implementation on a testnet or fork and point a forked proxy at it to confirm everything works with real state. Queue the upgrade via timelock (if you use one) to give a safety window.

- Execute: Use a script or admin UI to perform the upgrade transaction (for Transparent, through the ProxyAdmin contract’s

upgradefunction; for UUPS, by callingupgradeToon the proxy via the admin; for Beacon, by calling the Beacon’s upgrade). Consider pausing the system if you have that ability, during the execution of the upgrade, as an extra safety measure. If the upgrade includes new initialization (e.g. setting new variables), call the appropriate function (oftenupgradeToAndCallcan do this in one step).

- Verify: Immediately after upgrading, do sanity checks: call a few critical functions to make sure they return expected values (or run a small batch of read-only tests against the upgraded proxy on mainnet fork). Check that metrics or invariants hold (for instance, total supply of a token hasn’t changed unless intended, etc.). Update any documentation (docs or README) to reflect the new logic if user-facing behavior changed. Finally, if all looks good, unpause the system (if you paused) or proceed with normal operations.

Following this checklist can make upgrades a routine, predictable part of your development lifecycle rather than a fire drill.

Catch Before You Release

Upgradeability is a powerful tool when implemented correctly and a threat surface multiplier when implemented incorrectly. It’s important to treat every upgrade like a release, not an edit.

Octane’s tailor-made detectors catch these exact bugs – non-atomic proxy deployments, storage layout breaks, missing UUPS guards, and unsafe `delegatecalls` – and offer one-click patch diffs you can apply right away.

The result is upgradeability that really scales: predictable, auditable, and safe.

Schedule a demo today for a hands-on experience of what Octane can do for your smart contracts – upgradeable or immutable.

FAQs

A contract deployed behind a proxy that holds state and delegates calls to an implementation via delegatecall, so you can swap logic while keeping the same address.

Transparent: Upgrade functions live in the proxy and are callable only by an admin (often via a ProxyAdmin). It’s simpler and slightly higher on gas usage for regular calls. UUPS: Upgrade logic lives in the implementation contract itself (with an upgradeTo function). It’s lighter and more flexible long-term, but it requires you to implement access control on the upgrade function (and to be very careful not to accidentally disable the upgrade mechanism).

EIP-1967 defines standard storage slots in the proxy’s storage for the implementation address and the admin address. This prevents clashing with application storage (by using unlikely slot values). EIP-1822 (UUPS) defines a pattern where the implementation contract has a proxiableUUID and an internal upgrade function, enabling the Universal Upgradeable Proxy Standard. It’s basically the formalization of UUPS proxies.

Because the proxy never calls the constructor of the implementation. The constructor runs only when the implementation is deployed, which the proxy doesn’t utilize. Instead, use an initialize function (marked with the initializer keyword from OpenZeppelin) to set up state. And to prevent anyone else from initializing the contract later, call _disableInitializers() in the implementation’s constructor (this locks the contract so initialize can’t be called again on the logic contract itself).

With Foundry: install the openzeppelin-foundry-upgrades package, import openzeppelin-foundry-upgrades/Upgrades.sol, and use the provided library in your Foundry scripts or tests. For example, Upgrades.deployUUPSProxy(myContract, initializerArgs...) will deploy and initialize a UUPS proxy, and Upgrades.upgradeProxy(proxyAddress, MyContractV2) will perform an upgrade (with safety checks for you). Foundry will check storage layouts and initializer usage automatically during these calls. Just be sure to include the UUPS modules in your contracts (e.g. inherit UUPSUpgradeable and implement _authorizeUpgrade). With Hardhat (using OpenZeppelin Hardhat Upgrades plugin): in your deployment script, you can call await upgrades.deployProxy(MyContract, initArgs, { initializer: 'initialize' }) to deploy a proxy and call initialize with initArgs. Later, use await upgrades.upgradeProxy(proxyAddress, MyContractV2) to upgrade to a new implementation. The plugin will refuse to upgrade if you made a storage layout mistake or if you forgot to call an initializer, etc., providing a nice safety net.